Buffalo bayou’s waters flow east for more than 50 miles from fast-vanishing western prairieland, through Houston’s centre and out to its heavily industrial ship channel.

Long before the city’s tangle of freeways were built, the bayou’s existence helped draw settlers in the 19th century. But after thousands of homes flooded this August as Hurricane Harvey ravaged the city, proximity to water is increasingly seen as a liability.

More than 400,000 homes sit in the watershed of the bayou, which has become a focus of angst regarding how and where to rebuild, and whether Houston’s economic model – which helped it to become the fourth largest US city – is sustainable in the climate-change era.

“I think Houston’s at a turning point in its history,” says Jim Blackburn, an environmental lawyer and co-director of the Severe Storm Prediction, Education and Evacuation from Disaster Center at Rice University. “I think it could be on the forefront of the resilience movement of the 21st century and redefining how cities deal with these severe storm events, which are becoming much more commonplace.”

The alternative, Blackburn adds, is “we do nothing and frankly begin to see the economic decline” of this oil and gas hub, where there’s growing scrutiny of the rapacious development – and accompanying jobs – that once meant a chance of the American dream for so many.

After Harvey, will families and workplaces be safe the next time the rains come?

“Previous generations understood that you came here to make money and that was it,” says Susan Chadwick, executive director of Save Buffalo Bayou, a local advocacy group.

The notion that Houston could be pretty as well as practical came relatively recently to a city where a climate-controlled tunnel system links 95 blocks so that office workers need not venture outside. “People don’t come here for the nature experience – never did. It was not a hospitable place. It was a place you’d pave over,” she says.

I meet Chadwick on the bayou’s south bankon a sunny Sunday morning, and in this particular section, 15 miles west of downtown, it is a secluded and idyllic scene: blue sky visible through a canopy of trees, little noise apart from the puffing of occasional joggers and cyclists and the gurgling of turbid waters, perhaps hiding turtles, alligators, snakes, catfish and river otters.

- The aftermath of Hurricane Harvey

Yet these wealthy residential neighbourhoods, barely visible from the water’s edge above steep grassy berms, were some of the most devastated when the deluge came at the end of August.

Driving around, it looks as though normality has returned. But a few months ago, it was not untypical to find residents living among salvaged possessions in rooms with stripped-out floors and walls, or a For Sale sign lying in a puddle.

“They should never have allowed people to build so close to the bayou,” says Chadwick.

Victims of the flood

During Harvey, Axelle Bouleau had to watch via a security camera feed as the flood waters rose in Bonjour & Bienvenue, a French language centre in a strip mall west of the Barker reservoir.

After all the 16-hour days, weekends and evenings spent launching her business, Bonjour & Bienvenue was wrecked by over two feet of water. “It was very emotional because so much had been put in to get this started,” says Bouleau.

At first the worst of the rains passed and water had not seeped in. But then came a decision from the US Army Corps of Engineers’ to start releases from Barker and Addicks reservoirs, deliberately pushing water into the Buffalo bayou rather than risk uncontrolled overflows that might have caused further harm in central Houston and put the dams at risk of failure.

The reservoirs were built in west Houston in the 1940s to stop excessive water rushing along the bayou towards downtown. At the time, they were ringed by undeveloped land. Since then, despite Houston’s abundant space, thousands of homes and businesses have been built within the reservoir’s release boundaries.

Not that most people knew. Neither Bonjour & Bienvenue or the mall’s owner had taken out flood insurance. “This was not a flooding zone,” Bouleau says.

When the screen image cut out, she knew that the inundation had risen to the height of the plug sockets. It stayed for five days, destroying $25,000 worth of equipment. The first time she saw the damage in person, she got there by boat.

Months later, a 4ft model of the Eiffel tower was just about all was left inside the stripped-out unit, and classes were being held in the back room of a chocolate shop. The garden was cluttered with fridges, wood and other junk

“Changes need to be made, because I unfortunately think that we will see this kind of weather again,” Bouleau says.

Bouleau and her husband arrived 16 years ago for work. They benefited from cosmopolitan demographics and economic prosperity and became part of the city’s success story.

But Harvey was the third significant flood in three years, calling into question whether a laissez-faire boomtown mentality in a state that touts its low-tax, business-friendly credentials is compatible with flood control strategies requiring long-term vision, billions of dollars in public spending and firm governmental oversight of private developers.

Working with nature

Some of the most dramatic images from Hurricane Harvey, those wide-scale photographs of treetops poking above the flood with the city’s skyscrapers in the background, came from a location designed to work with, not against nature.

Part recreational attraction, part flood-control device, Buffalo bayou park is a 160-acre green space hugging the water that was completed in 2015. A symbol of Houston’s realisation that to attract and keep residents it must offer quality of life as well as job prospects, it was made with submission to water in mind and has flooded three times in its short history.

- Houston’s bayous … two months on. Drone footage by Van Williams/Envision!

Anne Olson is president of the Buffalo Bayou Partnership, which runs the park. “We know it’s in a floodway, so we planned it knowing that it would be underwater,” she says at the Partnership’s downtown base close to Allen’s Landing.

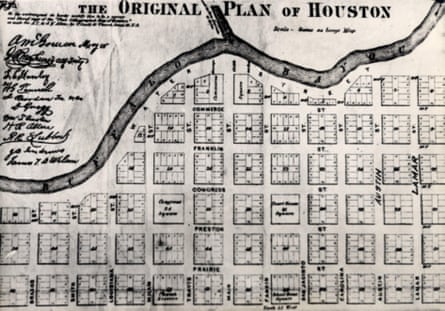

Here, a marker commemorates where two brothers from New York bought land in 1836 and opened a dock, starting an association with maritime commerce that would lead to the creation of a ship channel to the Gulf of Mexico, which is now home to one of the nation’s busiest ports and lined with refineries and petrochemical plants.

The bolted-in benches stood firm during Harvey; vulnerable features such as the perennial gardens were planted on high ground. Still, some segments of the park proved hardier than others.

One afternoon in mid-November, a few joggers trot past dismembered trees, white-grey sediment stacked on bald banks resembling sand dunes, and dump trucks removing silt and debris. Silt is piled up to 6ft in some areas and repair work will probably take until the spring.

“Houston has a short memory and they’re used to so many floods,” Olson says. “I’m hoping that there is a strategic plan in place, a vision.” A meeting she attended in October with business people and officials about improvements to a downtown street gave her hope.

“They were bringing things up like detention and pavement that will absorb water,” she says.

- An 1869 map of Houston and the bayou. Photograph: Alamy

Harvey is delaying the public engagement process for the partnership’s next big project, revitalising a portion of the river east of downtown surrounded by semi-derelict neighbourhoods, wasteland and industrial facilities. “We need better data. We feel we need to buy wider swaths of property to put our trails on. Before, we only were purchasing 30ft easements – now we feel we need probably about 90 or 100ft,” Olson says.

Returning developed areas to nature to act as riparian buffer zones – interfaces between land and water – sounds like an obvious option, but with no state income tax in Texas, property tax is the main revenue generator for municipalities; giving the water more space by limiting private development would mean limiting returns.

Tory Gattis, an urban strategist, co-wrote a paper arguing that the region proved impressively resilient given the storm’s unprecedented scope and the size of the population.

Roughly half the 80-odd fatalities occurred in Harris county, while “95% of the city bounced back pretty quickly – not to dismiss those people that are dealing with very hard situations,” he says.

Gattis is sceptical that minimal zoning regulations or covering absorbent wetlands with concrete as the suburbs stretch outwards did much to amplify Harvey’s wrath. “I don’t think that wholesale change [in response to Harvey] is something we necessarily need,” he says. “Much of the world is dealing with a housing affordability crisis and Texas is not, and Houston specifically is not and a big part of that is the flexibility of our allowing developers to develop and supply to keep up with demand in ways that the coasts haven’t been able to do.”

Gattis is, though, an advocate for stronger defences, like the exterior rising gate system installed by hospitals in the world’s biggest medical complex after a severe hit from Tropical Storm Allison in 2001.

“There are three great forward-looking investments this city made in its history: the ship channel, the Texas Medical Center and Nasa. They helped shape this city. I think the fourth one is going to be this resilience infrastructure after Harvey,” he said. “If we don’t do it then we are at risk – will people invest here?”

- A jogger in Buffalo bayou park in September. Photograph: Jon Shapley/AP

It is still too soon to tell whether talk will translate into action, and whether a city obsessed with creation can shift its mentality to focus on preservation, directing its resources and ambition towards taking better care of what it already has.

There are already hints that the most ambitious plans will be scuppered by financial constraints. Texas’s Republican governor, Greg Abbott, flew to Washington in October to ask for $61bn in federal infrastructure funding, including $6bn to purchase land around Buffalo bayou and the reservoirs and $12bn for a “coastal spine” barrier to guard against storm surge that, in a worst-case scenario, would rush through Galveston Bay and into the ship channel, overwhelming the industrial plants and causing the biggest environmental disaster in US history.

Abbott, though, declared his unhappiness a couple of weeks later when the White House proposed only $44bn in relief for Harvey, calling the spending plan “completely inadequate”.

A proposal for a third reservoir – an idea dating back to the 1940s – is gaining traction. Ed Emmett, a senior elected Harris county official, has called for quick buy-outs for structures that flood frequently, along with an expansion of the capacity of existing channels, better warning and risk analysis tools, and a refurbishment of existing reservoirs.

Chadwick, the advocate, would like an emphasis on preserving wetlands and storing rain where it falls using neighbourhood-level solutions such as permeable sidewalks, green roofs and parking lots designed to hold water – rather than putting all the effort into managing strong flows once they are in the river.

Similar approaches were embraced by Rotterdam in the Netherlands, which is seen as a model for future-proofing a flood-vulnerable city. China has a “sponge cities” programme, while Philadelphia is busy planting “rain gardens” next to Interstate 95.

Harris county is studying whether adding detention basins – excavated areas installed on, or adjacent to water – along the Buffalo bayou could help.

But Chadwick is doubtful that large-scale projects will justify their cost, and is against alterations that will sacrifice vegetation to bulldozers, such as chopping down trees to shape the wilder parts of the bayou into landscaped channels.

“This is an ancient river. You have to respect it. It’s going to do what it wants to do,” she said. “It’s a living thing. I just can’t let them kill this river, it has a soul and a force.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, and explore our archive here